BISHOP TEIXEIRA Biography

A Biography ofThe Most Reverend Filipe Teixeira, OFSJC

The young men sitting around a table in the offices of St. Mary's Episcopal Church in Uphams Corner are angry. The Feds are cracking down on suspected gang members in the neighborhood, and although they look like typical city kids in their jeans, jackets, and red Sox caps, they're far from it. Ranging in age from 12 to 32, all have been arrested at one time or another for crimes ranging from robbery to a stabbing. All are currently on probation. All were born on the island nation of Cape Verde off the west coast of Africa, which means the increased legal scrutiny could get them deported."Man, they're trying to smoke us," says Roberto, a 25-year-old just released from prison. "How they gonna help us by deportin' us?"Angel, a 32-year-old father of three who looks about 19, chimes in. "Same thing happened with the Irish, the Puerto Ricans, the Blacks, and now us." They may be aware that they've messed up, but the also firmly believe that as recent immigrants who belong to gangs, they are easy targets for law enforcement.

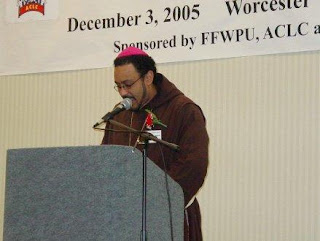

Listening to is all is Bishop Filipe Teixeira, dressed in a short-sleeve shirt and black slacks, calmly resting his elbows on the table and his chin on his folded hands. He looks slightly younger than his 37 years, and his closely cropped, black hair and sculpted goatee make him look more like a basketball coach than a religious leader.He acknowledges the frustration of his charges, all members of the Young Cape Verdean Club that he started in 2000. His voice never rises above a quiet conversational tone, even when striving to make a point. And his prowess with language allows him to slip in and out of Crioulo, the native language of Cape Verde."So, what can we do to help the community?" Teixeira asks the group. "What message can we give to improve the situation?"The young men aren't interested in Teixeira's sunshine policy. They've got self-preservation on their minds, and right now, they're more concerned with getting home without being shot and finding work with a prison record. "Look, I want to help my community," says Roberto, "but first I gotta help myself.""Roberto's had a hard life," Teixeira says with a sigh after the meeting. "He's seen things in life no one at that age should have to see."The same could be said for Bishop Teixeira. Over the past six years, he has carved a niche for himself as a minister to Cape Verdean immigrants in Boston. Last summer, with a marked rise in violence among the youth his ministry targets, Teixeira emerged as a leading voice for a community that heretofore had none."He's somebody that stands by his word," says Angel. "That's something you won't find in a lot of people."From attending the wakes of shooting victims and holding community meetings to advocating on behalf of Cape Verdeans in the criminal justice system, Teixeira works tirelessly to ensure that this community not only survives, but thrives in their new land. He is slowly building a bridge between law enforcement and the youth for whom the streets of Dorchester are both a home and a battlefield.

It is a mission he's been following for most of his life, though it took many years to crystallize. Now a bishop in the Catholic Church of the Americas, his drive to work on behalf of the marginalized in society is rooted in his Roman Catholic upbringing.His parents were both churchgoers, but the religion took a much stronger hold on young Filipe. As a child in the west African nation of Angola, he was drawn to priests and nuns the way American children are drawn to firefighters or baseball players. He stills remembers the reverence he held for Father Alberto, the pastor at Sao Paolo Church in the Angolan capital, Luanda."I wanted to grow up to be just like him," says Teixeira. "I thought it was the only way to get to heaven."Father Alberto was a Capuchin Friar. The order, founded by St. Francis of Assisi, established a mission in Angola during the height of Portugues colonization. Teixeira was enamored with the simplicity and humility he saw within the order. "They were truly what it means to be a son of Christ," he says. "They nourished my vocation."

In the late 1970s, Sao Paolo was taken over by the Salesian Brothers, another Italian religious order. Though still determined to become a Capuchin, the adolescent Teixeira spent a great deal of time with the Salesians, who introduced him to the life and works of St. John Bosco. "His life influenced a lot of what I'm doing," says Teixeira, "because he was assigned to young people, high risk kids.As founder and program director of the Young Cape Verdean Club, Teixeira works with high risk kids every day. In Dorchester, violence is a fact of life for even the youngest immigrants. The need for a sense of belonging as well as protection has led many Cape Verdeans to join gangs in much the same manner as generations of immigrants before them. The crews are less organized and usually unnamed, although police have taken to identifying them by the streets they congregate on, like Stonehurst or Wendover.Along with the hardships faced by any youths growing up in a hardscrabble urban neighborhood, young Cape Verdeans are caught in a legal and diplomatic stranglehold. If convicted of a felony, the federal government can move to have them deported to the nation of their birth, a land they don't remember and have no friends or family in. Teixeira spends several days a month at the federal court in Government Center advocating for kids caught up in a legal system they don't understand."I'm trying to be there for those who can't cry loud enough to be heard," he says.Teixeira's empathy for the victims of street violence is rooted in his own childhood, one steeped in the horrors of war, but also in perseverance. He was born the eldest of 10 children to Mario and Maria Teixeira, Cape Verdeans living in the Cuanza-Norte region of Angola, in 1966. Teixeira's father was in the Angolan military, which at that time was under the direction of the Portuguese. He was also a farmer, and owned his own land.

As is the custom in many African societies, Maria Teixeira sent her first-born son to live with her mother when he was just three-months old. "All her kids moved away and she was alone," he says. "So I went to live with her." There was no separation anxiety, as his grandmother lived only 30 minutes from his parents by car, and his father would visit on an almost daily basis.Teixeira's grandmother was a Jehovah's Witness and would occasionally host Bible Study at home. Yet on those nights she insisted young Filipe go off to the nearby chapel and pray the rosary. "To this day I still don't know why," he says. "I mean, she loved me. I was one of her first grandchildren. But she never let me sit down with her and the others and read the Bible.In the 1960s and 70s, Angola was beset by a war for independence led by three rival factions -- the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA), the National Union forthe Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), and the Popular Liberation Movement of Angola (MPLA). The Portuguese left Angola in 1975 without formally handing the reins of power to any group. This left a violent struggle that led to one of the most profound experiences in Teixeira's life.Believing the MPLA had taken root in Cuanza-Norte, the FNLA attacked Teixeira's village. Neither he nor his grandmother had time to gather up any belongings, and Teixeira was separated from her while running through a forest, following his neighbors but unsure of his destination. At one point, a group of Angolan villagers seemed to beckon the group to safety."They said, 'Look, go in this direction,'" remembers Teixeira. "The enemy is not here."Teixeira and his neighbors ran straight into an FNLA ambush, and the majority of the group was mowed down in a hail of gunfire. Miraculously, Teixeira escaped and ran alone for several hours, crossing a river at one point. He managed to climb up the side of a nearby hill and met up with another group that included his grandmother. "Here I came, all scratched up, you know, bit by ants. And I met my grandmother there. I said, 'Whoa!'"Teixeira had no idea where his parents were at that point. As it turned out, they had already fled to Luanda in the south. His father used his military connections to find Teixeira and his grandmother and put them on the first train back to the capital. They had lost everything -- their home, their money, their clothing -- but they were safe. After staying with the Red Cross in Luanda, the Teixeiras moved to Cape Verde and spent the next two years as refugees."I saw a lot of people get killed," Teixeira says of the experience. "I still have nightmares about it. It's still very much alive for me after all these years."Teixeira says the nightmares are very involved and sophisticated, and he always is the hero. "I'm always the one who fights and wins the war," he says. "I'm always running, climbing, and so forth."During his stay in Cape Verde, Teixeitra sought solace in the Church. It was around this time that he started to feel the call to a religious life. He enlisted as an altar boy in the local parish and fell under the tutelage of a Father Arlineo, who could take Teixeira to the small villages where he ministered.

By 1977, the situation in Angola had settled down enough that the Teixeiras could return. Mario Teixeira, the one-time farmer, found work in the country's new Department of Agriculture. Filipe, meanwhile, began spending significant time with the Capuchins and Salesians. At 15, he enrolled in the local seminary and began to study for the religious life.At 19, he came to the United States to complete his studies. His parents hoped that he would lose interest in a lifestyle that demanded so much discipline and sacrifice. "Being a priest or a bishop, there is not much you can do to help your family financially," says Teixeira. "And the expectation is that the first child should be the man of the family."He lived and worked at St. Patrick's Church in Roxbury, and it was there that he first saw a need for a voice in the community on behalf of Cape Verdeans. "That's where I really got the favor," he says. After six months, he went to Cape Verde for a year and was scheduled to go to Italy after that, but through fate or fortune, was sent back to the United States.Teixeira lived with the Scalabrini Fathers in New York and studied theology at St. John's University. After receiving his Bachelor's Degree, he was accepted into St. John's Seminary in Brighton and began to prepare for the priesthood. His childhood dream of following in Father Alberto's footsteps was close to being realized, but his experience at the seminary would change his calling forever.When he entered St. John's, Teixeira was the only Black person there. He felt it immediately, and he also felt out of place being so poor and yearning for a simple life while studying with seminarians who had their own cars and cell phones. He sensed animosity on the part of other seminarians, particularly when he started to mention his feelings to some of the faculty. Several of the faculty lent a sympathetic ear, but others wrote it off as a problem of Teixeira's own making.Teixeira was a student of the Black Liberation Theology of Leonardo Boff, and he was not given over to remaining silent about the injustice he saw in Boston. "When I see discrimination, racism, I am outspoken," he says. "To them, it was a threat."He was sent to St. John the Baptist Church in Peabody for his pastoral year, during which seminarians engage in the day-to-day work of the religious life in order to cement their determination to be ordained. Among other duties, he taught Sunday School, took students on trips, organized wakes and funerals, visited nursing homes, and kept house in the parish rectory. The predominantly White, working class congregation had nothing but love and respect for him, according to Teixeira, but he never felt quite at home."I thought to myself, 'This is not reality. This is not how the whole archdiocese will treat you'," says Teixeira.In addition to smarting from the racism he experienced at the seminary, Teixeira felt the language skills he had acquired over the years were not being utilized in Peabody. He had mastered Portuguese, Spanisg, and French, as well as several African languages, but was limited to using English in the small seaside town. "I felt like the archdiocese didn't know what they wanted from me," says Teixeira, "but I knew, as a Black man, I had no future here."

The epiphany hit him after Mass one Sunday morning. While the pastor of the church, Father John McDonald, was out on the front steps shaking congregants' hands and wishing them a good day, Teixeira bounded up to his third-floor rectory room, packed his suitcase, and called up his friend Jovino Senedo and asked him to pick him up.As Senedo pulled up to the church in his van, Teixeira said good-bye to Father McDonald and to the Roman Catholic Church as well."I was getting mixed messages," said Teixeira. "There were people who loved me and who saw that I had great things to offer. But there were others who saw me as trash. And I didn't see God in the midst of all that."

Dejected and confused, Teixeira spent several months at Semedo's Roslindale apartment. He stopped attending Mass altogether and got a job with the State Division of Youth Services. Teixeira was disappointed that his dreams of becoming a priest were dashed, but he still felt a calling to serve the Cape Verdean community in Massachusetts.He went to Hartford, CT, one day to visit a friend. They were walking through the park when Teixeira spotted a flier on the ground for an Independent Catholic Church. Intrigued, he called up the church and asked to meet with the pastor. Soon, he was introduced to the bishop and he began spending every week end in Hartford, just to go to Mass and work at the church. In the independent Catholic Church movement, Teixeira saw the simplicity and devotion to the poor and outcast that he felt was missing in the Boston Archdiocese.Having already completed his theological studies, Teixeira was moved to join the independent Catholic church and was ordained a priest on May 11, 1997. "When you are called," says Teixeira, "no matter how far you go, you always come back."Wanting to return to the community he felt most connected with, he founded the Church of St. Martin de Porres in Dorchester in 1997. The parish shares facilities with St. Mary's Episcopal Church. As crime rates among the youth of the neighborhood rose, other community leaders expressed exasperation at the lack of resources to deal with it. The police could only arrest the offenders and convictions on felony charges usually led to deportation.In 1998 Teixeira decided to found the Young Cape Verdean Club. At weekly meetings, Teixeira counsels young men (and sometimes women) on staying out of trouble and maneuvering through the federal and local legal systems. He holds citizenship classes for both youth and their families, helping them wade through the often unwieldy immigration process. He teaches English as a second language for six hours a week and organizes tutoring sessions in a wide range of school subjects.Named a bishop in the Catholic Church of the Americas in 2001, Teixeira looks forward to the day he can hand over the reins of the parish to someone else. "I want to get back into community life and leave the administration to someone else."

Along the way, Teixeira has experienced his share of controversy. He was arrested in 1999 on charges of failing to identify himself to officers investigating a street fight (he denied he was ever asked for identification). Some members of the community were upset to read his comments in the Boston Herald this October, endorsing the arrest and indictment of federal prosecutors of 13 suspected gang members on racketeering and murder charges."It's a good step," Teixeira told the Herald. "It's going to come down and teach some young men and women about justice, about law."

One of Teixeira's Dorchester neighbors, who lost a son to gang violence last summer, expressed concern about the Bishop's frank speech, "She said, 'Bishop, no, you're going to get killed,'" says Teixeira. "She was very concerned about me."Yet Teixeira shrugs it off with a laugh. "Look, I'm a child of war. I was born in war, I was raised in war," he says. "Why be scared now? My only fear is not being able to help people."

Comments

+ Dom Teixeira, OFSJC